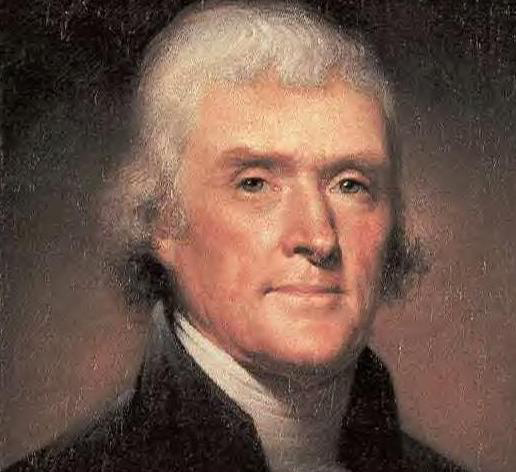

Thomas Jefferson did not have a very high view of the clergy as a profession. Throughout his life he referred to all clergy, including Protestant pastors, as "priests." The term, in his context, was not a compliment. Jefferson believed that priests, like kings, were enemies of individual freedom, and that such doctrines as the Trinity were simply used by the clergy to retain their manipulative power over the people. In a letter to John Adams, Jefferson wrote, "It is too late in the day for men of sincerity to pretend they believe in the Platonic mysticisms that three are one, and one is three; and yet that the one is not three, and the three are not one.... But this constitutes the craft, power, and the profit of the priests" (Mapp, The Faiths of Our Fathers, p.11). Jefferson believed that the power the clergy exercised historically in Europe and the colonies was enough of an argument to exclude them from holding public office. It must be said, however, that while Jefferson was distrustful of the clergy as an institution (especially Catholic priests-- Jefferson had little good to say about Catholicism), he did speak well of individual "priests" who did much charitable good in the community, and he was good friends with a liberal minister and scientist, Joseph Priestly. (The irony of Priestly's last name should not be missed.)

Thomas Jefferson did not have a very high view of the clergy as a profession. Throughout his life he referred to all clergy, including Protestant pastors, as "priests." The term, in his context, was not a compliment. Jefferson believed that priests, like kings, were enemies of individual freedom, and that such doctrines as the Trinity were simply used by the clergy to retain their manipulative power over the people. In a letter to John Adams, Jefferson wrote, "It is too late in the day for men of sincerity to pretend they believe in the Platonic mysticisms that three are one, and one is three; and yet that the one is not three, and the three are not one.... But this constitutes the craft, power, and the profit of the priests" (Mapp, The Faiths of Our Fathers, p.11). Jefferson believed that the power the clergy exercised historically in Europe and the colonies was enough of an argument to exclude them from holding public office. It must be said, however, that while Jefferson was distrustful of the clergy as an institution (especially Catholic priests-- Jefferson had little good to say about Catholicism), he did speak well of individual "priests" who did much charitable good in the community, and he was good friends with a liberal minister and scientist, Joseph Priestly. (The irony of Priestly's last name should not be missed.)Jefferson loved what he called "the good and simple religion of Jesus." His problem was not with Jesus but with how, so he believed, his followers distorted his teaching. The two Christian figures Jefferson reserved his harshest literary venom for was St. Paul and John Calvin. For Jefferson, Paul turned Jesus, the great moral deistic teacher (Jefferson actually referred to Jesus as a deist), into a divine Savior who redeemed the world in slaughterhouse fashion for a blood-thirsty deity. Calvin added to Paul's distortion of Jesus with his doctrine of original sin, which erroneously claimed humanity's helplessness before God, and double-predestination in which God decided by fiat who was to saved and who was to be damned. Jefferson found all of this to be absurd.

Jefferson's most well known views on religion were his thoughts he offered on the Bible itself. Jefferson embraced the teaching of Jesus as simple enough to be understood by a child, but rejected what he could not stomach (his words) as the unreasonable parts of Scripture, particularly the Gospels’ stories of miracles including the resurrection. Near the end of his life, though it was a project started years before while he was president, Jefferson took scissors to the Gospels and cut out the parts of the four Gospels he believed to be the authentic teachings of Jesus and arranged them into a narrative of the "most pure, benevolent, and sublime [teachings] which have ever been preached to man." He did not allow the work to be published during his lifetime. (It was published after his death.) The final work, which came to be known as The Jefferson Bible, is still in print to this day.

Jefferson was extremely concerned with the practice or ritual of government, which undermined his exclusionary understanding of the separation of church and state. Both Presidents Washington and Adams had proclaimed national days of prayer, fasting, and thanksgivings. Jefferson stopped the practice during his administration because he said it was "too Christian a thing for the president to do."

___

from Allan R. Bevere, The Politics of Witness: The Character of the Church in the World.

No comments:

Post a Comment